Finding Product/Market Fit: Lessons From Two Startups, One Exit, and a PM Role at Facebook

The crucial question of finding product/market fit during the early stages of your startup - including practical tips on how to validate your hypothesis without sacrificing your entire runway.

In this article:

What product/market fit is, and why it matters

Identifying and validating product/market fit before building a product

Choosing the right metrics to measure PMF

What we can learn from LawGeex, Facebook Messenger, Airbnb, and Zappos

(This guide is broadly based on Guy’s conversation with Gil Hirsch on Od Podcast)

Meet the expert: Gil Hirsch is a serial entrepreneur, angel investor, and product advisor. He was the Co-founder and CEO of face.com, which was sold to Facebook in 2012. After the acquisition, he filled several product management roles at Facebook, including PM for Facebook Messenger. In 2017, he co-founded StreamElements, which he continues to lead as CEO.

Why Product/Market Fit Will Make or Break Your Startup

Marc Andreessen was one of the first to popularize the term ‘product/market fit’. In his famous 2007 blog, he wrote (paraphrasing Andy Rachleff of Benchmark Capital):

The only thing that matters [for startup success] is getting to product/market fit.

Product/market fit means being in a good market with a product that can satisfy that market.

While you might find variations of this definition, the core idea is that you need to be selling a product that the market actually wants. Without PMF, even the best technology and the most marvelous execution won’t convince buyers to give you their hard-earned money.

Being a solution looking for a problem has sunk many startups. You might have gotten away with it, temporarily, during the last few frothy years, in which some VCs were happy to pour money into any vaguely-interesting technology. But this is no longer the case, and even those startups that managed to fundraise without product/market fit will eventually hit a brick wall with their sales efforts. This will force them to make costly changes or attempt to raise additional capital at much-less favorable conditions.

You want to reach product/market fit early, rather than count on a pivot. Developing products is going to be your largest expense as an early-stage startup; you should be as certain as you can that you’re making this investment wisely.

“A good pivot is on the solution you offer, not the market”, says Gil Hirsch. “There is nothing worse than going into a market you don’t understand or haven’t validated. After you’ve made promises to investors, hired employees, and had them pour their passion into developing a product - you don’t want to stand there and tell all of these people you got it wrong and need to make a U-turn.”

3 Steps to Identifying, Validating, and Measuring Product/Market Fit

1. Get very, very specific about sizing the market

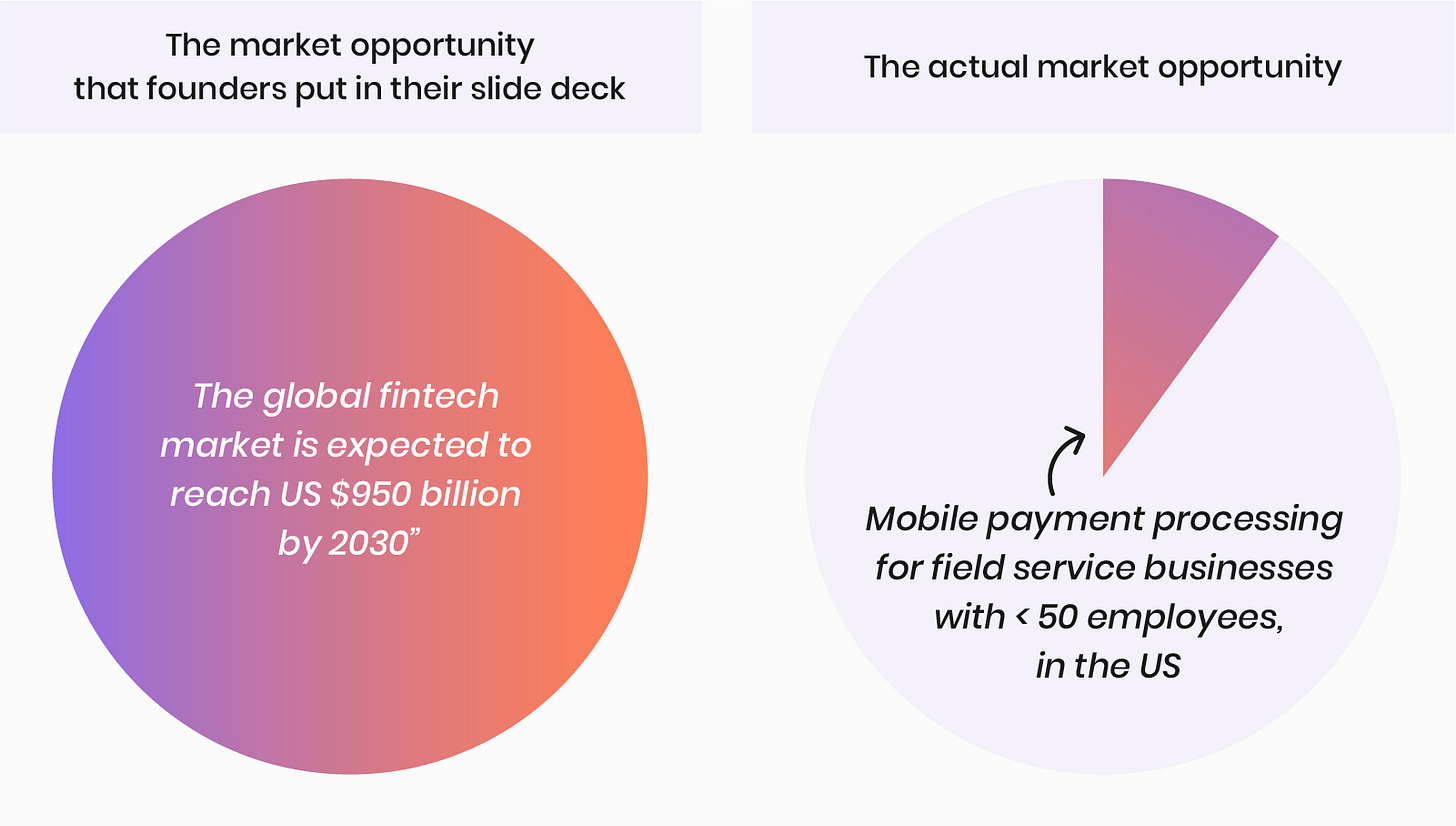

How to get market sizing wrong: Every startup tries to put a number on the market opportunity, but it’s rarely done in a serious way. For most founders, this is just an obligatory part of the ‘investor slide deck’ template that they prepare before a raise: you’re supposed to say that your startup is operating in a market that’s worth so-and-so billion dollars. They end up plucking the actual number out of thin air or some unscrupulous Google searches.

The problem isn’t just that investors can see through this BS (although they can) – it’s that you’re fooling yourself, and launching a product without a clear idea of the target addressable market.

How to do it right: You need to go much deeper than the generic market segment you’re operating in. Don’t talk about FinTech or e-sports. Find the specific customer you serve and why you’re doing what you’re doing, then make an intelligent attempt to quantify the sub-market you’re going to serve over the next 2-3 years.

Gil Hirsch: “It’s okay to also have a long term vision of the much-larger market you’re going to serve 5 or 10 years from now. The problem is most companies start and stop there, and end up with a half-assed, hand-wavey number that doesn’t really help them understand whether there’s a market for what they’re building.”

An example: LawGeex niched down before scaling up. Instead of looking at the entire LegalTech space, they searched for the sub-customer who has the most acute pain around the cost of preparing legal documents. Turns out, it’s not the law firms who charge customers by the hour for preparing these documents - but rather in-house legal teams. Then they could ask:

How many documents do corporate legal departments deal with?

Which documents are needed at a higher frequency?

Which are easier to automate?

Eventually, they managed to focus their initial market opportunity on automating NDAs for in-house legal teams in large American companies – a pinpointed, highly specific segment, which would be their gateway into the broader market.

This is the type of market sizing exercise that every entrepreneur needs to do. Find your sub-customer, then ruthlessly narrow down your focus to the problems that you are best suited to solve in the next few years.

In this context, Gil recommends prioritizing high-frequency problems (e.g., NDAs rather than M&A agreements), as these give you a built-in way to measure retention.

2. Validate your idea while doing the absolute minimum product building

Once you have a pretty good idea of your market, audience, and what problem you want to solve, it’s time to validate your idea - but wherever possible, don’t start building a product yet. Instead, what you want to do next is find a way to gather validation signals as quickly as possible.

You’re basically trying to prove that the intellectual exercise you did in the previous step is grounded in reality. There are a few ways you can go about this:

Sell the product before it exists (B2B). Reach relevant prospects, show them a slide deck, and try to turn it into a paid opportunity - a letter of intent (LOI), a pilot, or a paid proof of concept. Once you’ve repeated this process a few times, you’ll have proven that:

There is demand for the what you’re selling

You can capture this demand through sales and marketing

Only after you have this initial buy-in, you’ll start developing the product that you ‘sold’. Yes, you might burn some potential customers this way, but it will still cost you less than the months or years of the runway you’d burn on developing a product without PMF.

Do things in unscalable ways. Remember: at this stage, you’re not trying to prove anything except that the market is willing to pay for the solution you’ve envisioned. Sometimes the best way to do this is using various levels of ‘Mechanical Turking’ - taking orders from customers but fulfilling them manually instead of through the platform (which you haven’t developed yet).

There are a few famous examples of this:

Tony Hsieh launched Zappos with a landing page and a catalog and would fulfill orders by purchasing the shoes after the customer ordered them. The hypothesis he proved was that people were willing to buy shoes online.

The AirBnB founders started by doing a lot of manual work to create inventory, including physically going to the properties to photograph them. They did this to prove the hypothesis that people would pay to rent apartments from strangers.

Discovery calls. Reach your audience - for example, people who are using your competitors’ products - and interview them. Try to understand what guides their purchasing decisions, and where your idea could fit in.

If you already have a solution, you can of course try to sell it; but otherwise, Gil Hirsch says you can deliver value and “impress [your future customers] with your understanding of the opportunity. Give them value by telling them what other leaders in their industry are doing - which you will know based on your previous interviews and research into the market.”

3. Find the metrics that are tied to value (not revenue)

With your market size and opportunity validated, you want to find the one metric that best measures your progress toward capturing that opportunity. Gil Hirsch believes that this will rarely be monthly recurring revenue (MRR):

“MRR is a trailing metric. The customer might have already decided to churn, but you’ll only find out about this at the time of renewal. It’s a measure of your revenue, not the value your customers receive from your product.”

What would you measure instead? At Facebook Messenger, the answer was the number of daily messages sent. What are the advantages of this metric?

Unlike aggregates such as monthly active users, this metric would change daily. It allowed the Messenger team to understand the impact of their experiments and iterate fast.

It was closely tied to multiple strategic levers, including the engagement of each user with the app (which could be increased through features such as stickers and groups), and the size of the user base itself.

It was a proxy for the value users get from the app.

Don’t just measure yourself according to this metric. You want to measure your competitors according to the same metric, and you want to know both their and your performance over time.

Historical data will help you validate that you chose the right metric. Look at periods where you were doing well according to your metric of choice - was your business growing at that time? Did other KPIs improve?

So should you still measure MRR, MAU, or LTV? You should definitely measure these as well, and take them into account when you’re making product decisions. But you need to stay laser-focused on that one key metric that is closely tied to your product/market fit thesis, that is easy to measure, and that is sensitive to experiments and product updates.

Remember: PMF Doesn’t End at Series A

Think of product/market fit as an ongoing journey, rather than a single destination. It doesn’t end after you raise your Series A, or after you reach your first 10 or 100 paying customers.

The market evolves, your product evolves, your competitors catch up or fall behind, and new competitors emerge – all of these require you to continuously validate your hypothesis, and update your previous assumptions if they are proven wrong.

As you grow and acquire more paying customers, retention metrics become your key indicator. And here too there are many questions to ask: which cohort of active users do you measure when you talk about retention? What makes them active? And many others. But to keep things (somewhat) short, we will tackle these questions at another time.

Next Steps

Connect with Gil Hirsch on LinkedIn, or follow some of the cool stuff he’s doing at StreamElements

Listen to the full episode of Od Podcast for more great insights into product and strategy

Join our mailing list to get the next article in the series as soon as it’s published.

Great content.

the link to Gil's LinkedIn is broken (it's referring to this link instead: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1h-wnjdTnCCzfhDiIv5oMgBgDiwAWUhmd5K8arPr4s1g/edit#)