How Venture Capital Firms Think: A Crash Course for First-Time Founders

Masterclass, Episode 2: Understand how VC firms are structured, how they operate, and what drives them to make investment decisions.

Watch the video:

Episode Highlights:

If you’re launching your first tech startup, you’re going to be rubbing shoulders with venture capital (VC) firms. They are the movers and shakers of the tech industry in Israel, the US, and really everywhere there is a tech industry. VCs are responsible for the vast majority of capital-injected new startups – shaping the trajectory of countless businesses.

This Masterclass will help you gain a better understanding of the way VC firms are structured, how they operate, and what drives them to make investment decisions. By the end, you should have a better idea of what VCs are looking for, which will help you make better choices when approaching and pitching to them.

What You’ll Learn:

How VCs make money for themselves, and for their LPs

The interests and forces at play in an investment decision

What investors are thinking about when you’re pitching to them

Why does all of this matter to you as a founder

Meet the expert:

Guy Katsovich is the Co-founder of Fusion VC, Israel’s leading pre-seed platform and startup accelerator. Fusion has invested in over 100 Israeli startups, and in 2023 raised a new $20 million fund backed by Insight Partners and 70 serial entrepreneurs and industry leaders.

The Basics: The Structure, Goals, and People Involved in Venture Capital

Most founders have a pretty superficial understanding of VCs. They’re perceived as individuals who sit on top of an unlimited pile of money, waiting for the best and brightest entrepreneurs to give it to (based on the quality of their pitch, of course).

The reality is a bit more nuanced.

VCs are entrepreneurs. We tend to think of VCs on one side and founders on the other; but VCs are also founders – except that instead of building a company, they've launched a financial instrument. This business is backed by investors, who are usually institutional investors or high-net-worth individuals. The pitch from the VC to her investors is straightforward: give us your money, and we'll create better returns than other fund managers or investment channels you might be considering.

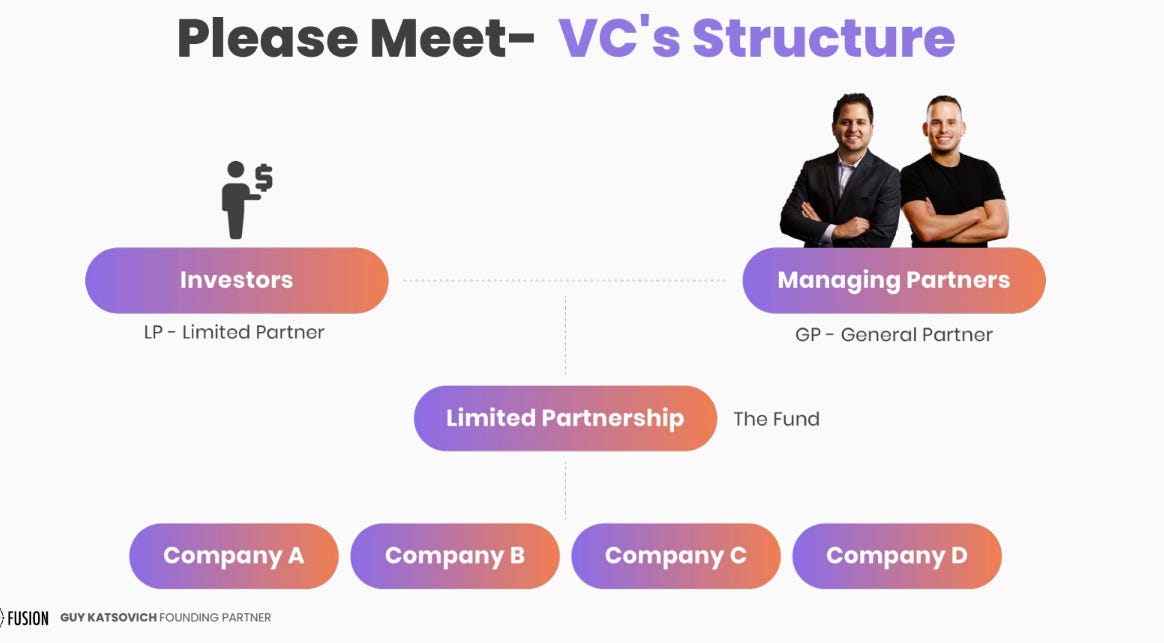

The individuals responsible for raising and deploying money within VC firms are managing or general partners (GPs), while those who invest in the funds are known as limited partners (LPs). As a founder, you’re going to be interacting with the GPs, and in all likelihood will never meet your LPs.

Like any business, differentiation matters. VCs will differentiate themselves through specialization in certain verticals, the expertise of their partners, or the stage they invest in. This is a key part of their fundraising pitch.

The VC firm is a limited partnership between the general partners and the limited partners. The money collected from the LPs goes into the fund, and the GPs deploy it into various assets – predominantly startup companies. GPs have the discretion to allocate the funds however they see fit, in line with what they pitched to their LPs (more on this below).

From there, the business model is pretty simple:

GPs take a fraction of the money as a management fee (typically around 2% for every year of the fund’s existence), while the remainder is invested in startups.

Profits are taken at a liquidation event - an exit or an IPO. Returns are divided between GPs and LPs, and the ratio is almost always the same: 80% goes to the LPs, and 20% is retained by the GPs).

The Investment Period

Every fund has an investment period – a predefined timeframe during which the VC firm actively invests in startups. There are two rationales for this:

It prevents general partners from simply sitting on the money and not deploying it (while continuing to take a management fee).

Investors want to see their capital put to work quickly as it affects their potential returns: a 2x return in 2 years is impressive; a 2x return in 20 years is probably worse than the S&P 500.

Why this matters: Investment periods typically last a few years; recently the trend has been closer to 2-3 years. If you come across a partner at a VC firm on LinkedIn or elsewhere, you should check when the fund was started and whether they are still within the investment period before sliding into their DMs. If it’s been more than five years, they’re likely more focused on managing and growing their portfolio (the harvesting period).

The Mandate

VCs have an investment mandate. This is the thesis that the GPs pitched to their limited partners, outlining the specific types of deals they believe will generate the best returns. The mandate defines the sectors, stages, and types of companies a VC firm is primarily interested in investing in.

Why this matters: You can get a pretty clear idea of a VC’s mandate by looking at its website and its investment history. If a VC firm has a mandate to invest in cybersecurity startups and you’re pitching a gaming company, you’re going to have a bad time. Your chances of securing funding are much higher when targeting VCs whose mandate aligns with your company’s industry, stage, and growth prospects.

(If exceptions can be made, they will be made for entrepreneurs with a proven track record, significant traction, or an exceptionally groundbreaking idea. As a first-time startup founder, it’s probably not going to be you.)

What VCs Want: Understanding the Incentive Structure and the Power Law Distribution

VCs are financial players. They want to yield in the form of high returns on their investments. Startups are a risky asset class, and investors need outsized returns to compensate for that risk. As a VC, most of your bets are going to be losers; when you win, you want to win big.

Limited partners typically expect 3-5x returns on their investments, at the very least. This expectation is the primary driving force behind VC investment decisions.

How often does this actually happen? Over half of deployed funds do not return 1x of what they raised; but as you approach the top of the pyramid, you’ll find firms generating eye-watering multiples of ROI.

This relates to the power law curve of VC investment – a very small percentage of firms capture a very large percentage of returns in the tech industry. In Israel, it’s the Wix and Mondays that create the multi-billion exits and make investors really, really rich; globally, it’s the Googles and Facebooks.

General partners also earn income through management fees, typically set at 2% per year during the fund's lifecycle (which would be around 10-12 years). These fees are intended to cover operational expenses – salaries, office space, and everything else required to keep the lights on and maintain a well-functioning VC firm capable of finding the best investment opportunities. Management fees also create an incentive for VCs to raise larger funds – and establishing a successful track record is key.

Where Things Get Tricky

Let’s do some math.

Suppose you’re a VC managing a $100M fund. 2% annually goes to management fees – over a period of ten years, that will be about $20 million. So you’re deploying $40-80 million in maybe 20 startups. You want to 3x your initial investment because that’s pretty much the minimum that LPs are expecting you to achieve. So you’re looking to generate $300M in revenue.

Now let’s say you do a great job negotiating, and manage to secure a 20% stake in all of your portfolio companies. In fact, you’re such a phenomenal negotiator, that you manage to hold on to the 20% stake in subsequent rounds, and are never diluted.

Even under these assumptions, you’ll need the cumulative sum of your exits to be $1.5 billion (remember, you want to make your $300M off of a 20% stake).

Now consider the power law: out of the 20 investments you made, most aren’t even going to make the money back. You’ll be very lucky to land one or two big exits or IPOs. Historically, we have not had many of these in Israel

And remember – the assumptions we made are ridiculously optimistic. In reality, you will get diluted. Later investors will have some kind of preference in profits. You won’t have a clean 20% stake in all your companies. But even under these unrealistic assumptions, you still need a billion-dollar exit from one of your 20 portfolio companies. If you don’t reach that, there’s no guarantee you’ll be able to raise another fund.

And what if you’re managing a larger fund? Funds in Israel are typically larger than $100 million; late-stage VCs need to deploy billions. And they still rely on that handful of oversized exits to make their money back – just at a much larger scale.

It’s not easy!

Putting it All Together: What the VC is Thinking About When You’re Pitching to Them

Now that you understand how VCs operate and what their incentive structure looks like, try to put yourself in the shoes of the general partner you’re pitching to.

They don’t actually care about your slide deck. They’re not going to invest in you because of how well you explained the TAM or the depth of your market research. These things do matter, they’re just not enough. The VC is looking to beat the odds that are stacked against them – and for that, they need to choose the companies that have a chance to make it big. More than big: huge. They need the next Wix. The next CheckPoint.

If that’s what your company is, you’re going to change this person’s life. You’re going to make them rich, and you’re going to be the logo they put on their slide deck for their next fund.

As founders, this is the story you want to tell. You need to convince VCs that you have the TAM, the opportunity size, the product, and the go-to-market strategy – all of the things that need to magically come together – and shape it into a coherent narrative, which ends with an exit that’s worth 10-100x their investment.

You need to be able to tell this story with a straight face – so you’d better start believing in it yourself.

Key Takeaways

VCs operate as investor-backed businesses, with managing partners (GPs) raising and deploying funds from limited partners (LPs).

Investment periods and mandates are important factors to consider when approaching VCs for funding.

VCs seek high returns to compensate for the risky nature of startup investments and to meet LPs' expectations.

The power law distribution of VC investments means that a few major wins are needed to generate significant returns.

When pitching to VCs, founders should focus on demonstrating the potential for huge growth and outsized returns on investment.

That’s a Wrap!

We hope you found this episode helpful. Here’s a sneak peak of what’s coming next:

All episodes are also available on Od Podcast.

Fantastic read, Guy! Love how you've unpacked the whole GP-LP dynamic and the VC decision-making process.